From Text to Tokens

2025-12-07

This post is based on chapter two of Sebastian Raschka's Build a Large Language Model From Scratch.

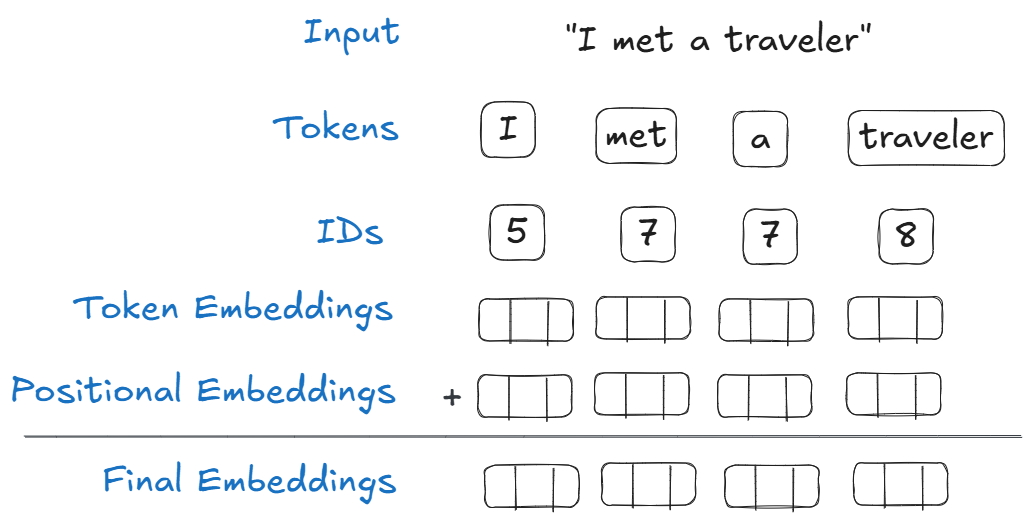

Tokens

When working with natural language, we need to convert words into a format suitable for training a model. This is done by taking words, and turning them into numbers through a process called tokenization.

Tokenization can be done very simply. We start by taking a body of text, and breaking it up into individual words. We then keep the unique words, and assign each a unique value, going from one to n. We can now use this table to convert any sentence into a list of numbers suitable for Machine Learning workflows.

For example, the sentence "I met a traveler from an antique land", can be turned into the following dictionary:

| Word | ID |

|---|---|

| a | 1 |

| an | 2 |

| antique | 3 |

| from | 4 |

| I | 5 |

| land | 6 |

| met | 7 |

| traveler | 8 |

The sentence can then be tokenized to:

[5, 7, 1, 8, 4, 2, 3, 6]

While simple, the solution above has one glaring issue. The table we use to tokenize words has a limited vocabulary. It can only convert words that is in the list, that is to say, words it has seen. One solution is to add support for special and unknown characters. However, an even more complete solution is byte-pair encoding.

Byte-pair encoding is a more through way of converting words into IDs. Instead of converting individual words, it takes parts of words, and turns those into IDs. For example, the word “traveler” would be sliced into “tr,” “avel,” and “er.” Then each of those would get assigned a unique ID. A more complete explanation is beyond the scope of this post, for now we can use OpenAI's tiktoken library.

Creating Input Pairs

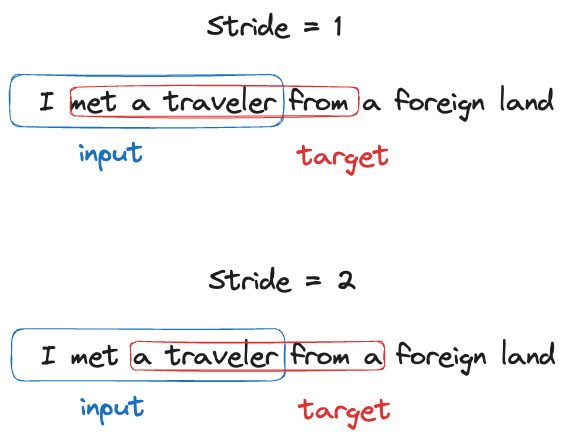

Once we’ve converted our sentences into IDs, we need to create the dataset we’ll use to train the LLM. As is the case with most training data there is an X and a y, where X is an input, and y is the target value.

For our X value, we start to slice our sentences up. For example, this can be an array of four tokenized words. Then our y is the input, shifted by some some “stride.”

Consider the sentence, “I met a traveler from an antique land.” For the sake of simplicity, we could create inputs with only four words. In this case, we would create an X that contained “I met a traveler.” Then we’d fill y with the output “met a traveler from.” This pair would then be used to train the model.

The numbers used above were arbitrarily chosen. You do not necessarily have to just have four words in your input – production-ready LLMs are trained on much longer contexts. Similarly, stride is another concept to be aware of. In the example above, we choose a stride of one. This means that we sifted our input by one to get our target.

Given the sentence "I met a traveler from an antique land", we can create the following input and target pairs:

| Input | Target |

|---|---|

| I met a traveler | met a traveler from |

| met a traveler from | a traveler from a |

| a traveler from a | traveler from a foreign |

| traveler from a foreign | from a foreign land |

| from a foreign land | a foreign land |

Token Embeddings

Now that we have our X and y, we need to create embeddings. These are just weights that are randomly assigned to start. The neural network will adjust these weights; think of embeddings as dials that will be tuned by the neural network during training.

Token embeddings are a just a large lookup table of weights that will be tuned. To start, we count the number of unique words in our vocabulary. This will determine the number of rows. Each word is gets its own row of embeddings. Next, we determine the embedding dimension, the number of columns. Finally, when the word appears in the X array, the model selects these embeddings.

For example, if there are ten words in our vocabulary, and we decide we want three embeddings, the final result is a 10x3 matrix. Where we have ten rows (one for each word), and three columns (weights).

| Word | w1 | w2 | w3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | 0.6 | 0.13 | 0.18 |

| an | 0.57 | 0.37 | 0.82 |

| antique | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.89 |

| from | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.72 |

| I | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.28 |

| land | 0.93 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| met | 0.22 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| traveler | 0.53 | 0.02 | 0.88 |

To create these embeddings we randomly generate an array of numbers. Each unique word is assigned an array of weights.

As an example, the word “traveler” might be assigned [0.53, 0.02, 0.88]. Now, every time the word traveler appears in a sentence, these weights are used.

Positional Embeddings

You might have noticed that words will always have the same wight. This can be problematic when dealing with language. The order in which we choose to use words can drastically alter the meaning of a sentence. To capture this positional data, we create positional embeddings.

The shape of the positional embeddings matrix is determined by the context window – or the maximum number of tokens the final model can handle in one input. For example, if we determine that our model will support 256 tokens, then our positional embedding table would have 256 rows. The number of columns (or dimension) should be the same as the token embeddings – we’ll see why in the next section.

Positional embeddings, like token embeddings, are randomly generated, and will be tuned during training.

In this example, we have a context window of four:

| Position | w1 | w2 | w3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 0.69 |

| 2 | 0.94 | 0.69 | 0.56 |

| 3 | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.13 |

| 4 | 0.5 | 0.17 | 0.96 |

A word appearing in the second position would have the weights [0.94, 0.69, 0.56].

Final Embeddings

To get our final embeddings, we simply add token embedding and positional embedding. Simple.